Today we commonly feel the urge to move faster – take notice faster, learn faster, decide faster and act faster. It becomes a struggle. Still we can’t just decide: let’s be faster. There are situations, behaviors, previous experience and other things slowing us down. Let’s gather some analysis on what are the common situations asking for faster action, and what could be the simplest solutions at hand helping us find a way to move in a Fast Forward way – e.g., quick decision making.

Our lives go on quickly. Market situation evolves and changes rapidly, business needs change. Decision about starting a new business, launching a project may be hard to make. Fast development of the situation makes it even harder, because we need to take risks resulting from the changes in account. Often “go” or “no go” decisions may take months or even years. Here we’ll talk about one of the ways of making the process faster.

One of the active parts in decision making is uncertainty. When the time comes, we don’t feel completely sure what to do. Let’s address this.

First of all - define: what kind of decision you want to make (or help someone make – he/she must provide this information). “As a result we want to go/no-go, choose partner etc.” Often problem is in an unclear definition of the decision to be made, like “we need to decide about the project” or “I must decide about business development”. That kind of description doesn’t reveal what exactly you’ll be doing. Rephrasing may help – “we need to decide: launch the project now, or delay till next year’s budget period” and “I will decide: does it make sense to make a full market analysis about the development of the new business branch for teenagers, or maybe it’s just isn’t worth it”. Much clearer and provides important clues – what you’ll need to make a decision.

Be sure to clearly define what kind of information you need to decide – “Knowing A, B and C I would decide this way”. Confirm how much information is good enough to make a decision and not to postpone it. Still some of the cases may lead to a need for more information – but gathering of it should be postponed. Don’t rush. Write down the needs, make a pause, review: if I have this information will I be able to decide? If you are not sure – ask yourself: what would make me confident?

Here’s a tip: in such situations it is good to do it alone (so that you aren’t bothered about an impression you may make on others) – or involve consultant, who may be able to help you formalize the process. By the way: I really believe that you do know what you need to make a decision, but it may be hard to understand yourself.

Plan how you can acquire chosen information – on a day-by-day basis. If it’s obvious that it would require more than a week – what checkpoint will be made in a week to make some kind of a decision? As an example, do we still need more information, or that we’ve already acquired is enough to decide on changes in required information or even say – “no go, it’s enough to see – it’s not going to work”. Stop wasting time on continuous research in the area. Often we have enough information to say: “enough, no go” or “Stop. Based on this we need to change our plans and so we need different information to decide on go/no go.”

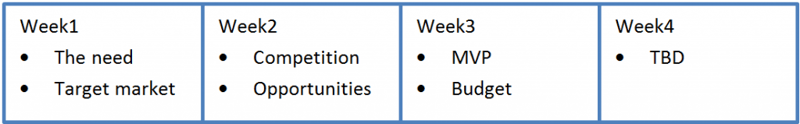

Plan ahead (and make it visual); write down information you need and plan, when it will be necessary and possible to get. You need to be realistic; this is how it may end up looking like:

After each of the iterations, remember to adjust the plan to meet the changed reality, to make the plan consistent with decisions you’ve already made thus far.

Here are the types of information you should know about:

- Confirmative: supports our choice or helps us make one; example: consumers require our solution (confirmed by prototype), they are ready to pay in accordance to our sales calculations, and there are not too many other solutions on the market providing the same benefits, etc.

- Declining: assumptions are wrong – stop everything, or adjust the plans and correct the information needs; example: in our planned solution area the market turns out to be crowded – is it worth to go on with this idea?

- Adjusting: based on this we will change our plans considerably or re-focus the information needs; example: in our planned solution area the market will be crowded in the next two years (brings up high risk of competition).

- Unimportant: brings almost no value – sometimes all three previous areas instead of clear answers brings this kind of a result. Sometimes areas of the research are poorly defined and therefore yield poor answers.

Focus on the first two types of information – it will shorten your decision making cycle!

Always perform milestone reviews on time – no excuses. Also allow yourself to decide: “we need more information on the subject”, or “we need more precise information”. In both cases provide precise definition of the need (or you’ll be researching and reviewing forever). Question yourself – will I be able to make a decision in a week if I had the information I requested? If you’re still not confident about answer – review the information need, again.

If you can’t get all the information as planned (and I assume – often it will be the case), try getting enough information to make at least a smaller scale decision; perhaps, you could gather precise information in a narrower area than originally planned? And a lot of imprecise information has much less value, than a smaller portion of more precise data.

For some of us the hardest part may be to say to ourselves: stop getting it perfect. Then stick with this thought: It’s as precise as it was requested, it’s enough to decide.

How to understand – are you progressing or procrastinating? Let’s define the failing.

Definition of the “fail”: we don’t have enough information on weekly review to make any kind of decision rather than to research for more, then what you have just gathered is not usable (keep in mind: it’s different than having enough to review and decide; it’s understandable, measurable, and based on this I decide to invest resources and gather more detail).

Reminder: if important information is available only after a long period of research – plan ahead, start the research now, in parallel with weekly preparations. Maybe it all will be thrown away because of a “no-go” decision on, say, third weekly review – it’s fine. In case of progressing till fourth weekly review – it will be needed.

Instructions: on review meeting analyze the results, not research the process. If you don’t trust sources – you had to require confirmative information ahead, not at the moment of the review. Sometimes people gathering information are seen as untrusted source, especially if information makes decision maker uncomfortable. Solution: don’t argue – you have almost no chance of winning (winning in a debate will probably be loss of trust in a long term); ask for trust criteria for the next portion of information (example: financial department should have approved gathered sales data).

Summary:

- Define:

- clearly - what will you be making a decision about,

- exactly what kind of information will be enough to decide,

- how much time is required to gather such information.

- If it’s more than a week, then split the process in the smaller parts, so that each portion of information could be acquired in a week, and this part will be enough to make some sort of a decision: go on with gathering of the information or make a decision to drop the subject altogether.

- Make a plan with exact activities (including involved people). Make sure you’ll have all needed resources. Don’t guess – make sure.

- Schedule regular reviews and do them (don’t postpone).

- Gather information.

- Review, decide. Adjust, if needed.

- Keep going – repeat previous steps (7-8).

- Make the final decision.

Remember, on a review meeting – make a decision. If you are not making a decision: read the previous sentence once again and redo the meeting.

If you have questions about the topic or would like to discuss case at hand – feel free to contact us!